Trees communicate and move

The time has come to fundamentally reconsider our relationship with nature. If you believe that trees don’t communicate or move, you’re mistaken. That’s what Italian biologist and botanist Stefano Mancuso explained in his influential 2018 book “The Incredible Journey of Plants.” It’s no coincidence that Mancuso is a close collaborator of one of the great landscape visionaries of our time, the Belgian Bas Smets.

Belgian Pavilion

Bas Smets, Belgian Pavilion

Together, they are working on the Belgian pavilion, with Smets as curator, at the Venice Architecture Biennale opening on May 10, 2025. The pavilion crystallizes all the landscape architect’s obsessions: how entering into communion with nature could help us avoid climate change and other natural disasters.

In this building, plants play a central role. Smets is known for harnessing their “intelligence” to purify air and regulate temperature. “You enter the pavilion and see an indoor jungle of 250 subtropical trees. You feel a freshness that contrasts with the heat of the Venetian summer. We’re aiming for a real understanding of plants, to empower them to regulate the pavilion’s indoor climate.”

Solidarity between trees

Bas Smets, Belgian Pavilion

To bring this to life, Smets also collaborates with computer scientist Dirk de Pauw, “who connects the natural intelligence of plants with artificial intelligence,” and with Kathy Steppe of Ghent University, who developed the sensors that gather the data. Smets speaks of “understanding the tree’s pulse.” He adds, “Just ten years ago, we had no idea that trees communicate through their roots. It took the research of Suzanne Simard [Professor of Forest Ecology at the University of British Columbia] to prove that trees help each other, even across species.

Thanks to the roots

Bas Smets, Belgian Pavilion

In winter, the fir helps the birch when it has no leaves and can’t photosynthesize. In warmer months, the birch, with its broad foliage, produces more sugar and in turn supports the fir. Our culture underestimates plants. We need to think about them differently—not as animals, but as beings that function communally, constantly interacting with their environment, thanks to their roots, leaves and flowers.”

Against all odds, this ever-humble enthusiast displays a rare optimism for our times. Through his methods, he believes that the resilience of cities is possible.

Renaissance Flemish paintings

Bas Smets, Belgian Pavilion

Smets was born into a well-traveled Belgian family, the son of an engineer father and a mother who introduced him to art. (He is also a connoisseur of gardens in Flemish Renaissance painting.) The vocation of this man with large, sincere blue eyes can be traced back to an extraordinary place on the outskirts of Brussels: the geographical arboretum at Tervuren. There, in 1902, King Leopold—infamous for more sinister reasons—imported a large number of trees from the New World, grouping them by geographic origin.

Shinrin-yoku

Arboretum, Tervuren

“From a young age, I noticed the different sensations that came from, for example, a forest of conifers versus a forest of beeches. I’ve always had a special affection for the beech tree which explores the unknown underground with its roots while simultaneously reaching for the sun. I love that dual movement.” With a wide smile, he brings up the Japanese concept of shinrin-yoku, or “forest bathing”—the idea that trees can heal.

Harvard GSD

Smets studied both engineering in Leuven and landscape architecture in Geneva, then founded his eponymous practice in Brussels in 2007. Since then, accolades have followed him. He has been Professor of Landscape Architecture at Harvard since 2023. Each year, he and his students take a city as a case study to assess its resilience in the face of climate change. Last year, it was Paris. This year, it’s Doha. “We’re tackling harder and harder cases,” he dares to say.

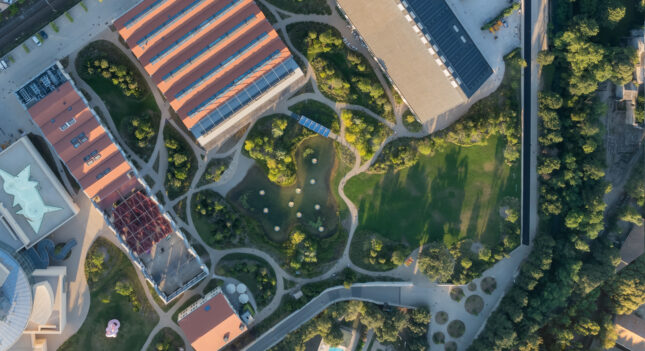

Luma, Arles

In France, it was collector Maja Hoffmann (See here an interview of Maja Hoffmann) who tapped him for her vast Luma cultural campus in Arles. Around Frank Gehry’s tower, Smets transformed the sweltering concrete floor of the former SNCF workshops into a cool summer promenade for locals.

La Defense

Eight years ago, he also worked in Paris’s La Défense district around the Trinity tower at the request of the developer Unibail. “It was 4,000 square meters of floating structures with a skyscraper in the middle, surrounded by other towers. We were elevated, with shifting winds and reflective surfaces everywhere… I thought: Everything here is mineral. It feels like we’re in the mountains. We needed to create the largest possible canopy so people could stroll under it protected. The trees we planted, particularly the alders, resist winter salt, grow in shallow soil and don’t contain allergens. Today, there are about fifty of them, standing 12 to 15 meters tall. The area has become a living space. Birds are coming back. You can hear the wind in the leaves. People come there to eat lunch.”

Notre Dame de Paris

Don’t expect Bas Smets’ green projects to be merely pretty or overly flamboyant. “Nature isn’t decoration. I don’t like this idea of just greening the city.” But, by his own admission, the project dearest to him today is the redesign of the public spaces around Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris.

Of course, working on a historic monument of such stature meant juggling city, national and even religious regulations. But Smets was quiet on that subject. He prefers to talk about the cathedral’s construction accuracy, its original ambitions, Victor Hugo’s idea of Notre-Dame as the belly of the city, and his desire to bring Parisians back to this tourist-saturated spot. “I lived in Paris for seven years and never lingered over there. Twelve million people visit Notre-Dame annually—that’s twice as many as the Eiffel Tower.”

Landscapes, in general, are long-term projects. The one he imagined for Notre-Dame will reach maturity in 2028. “We aimed to create a space that is both communal and climatic,” he says.

As a clearing

The square in front of the cathedral has been designed as a clearing that showcases the eastern façade. The trees provide coolness in summer and block cold winds in winter. First stage: At the reopening of the restored cathedral last December, visitors could already see the newly laid stone. “The square is as wide and long as the cathedral itself. We covered it with limestone slabs laid in a staggered pattern with fine grooves—an understated outdoor echo of the black-and-white checkerboard floor inside.”

The virgin at the exact center of the building

Ever mindful of heat waves, Smets also redirected a stormwater channel to allow a 5mm sheet of water to ripple across the square on demand, stopping 20 meters before the cathedral. “As though a storm has just passed, cooling the air.”

Smets became fascinated with the architectural details of the building. He points out a precise spot on the square, aligned with the statue of Charlemagne, from which you can see the image of the Virgin Mary, perfectly centered, in the window of the stained glass. “From that point, you realize the cathedral was built around the Virgin’s head, like an immense halo. And once you realize that, it’s a magical moment,” he says, visibly moved.

160 new trees along the Seine

To the south of the cathedral, along the Seine, he has designed a 400-meter-long garden planted with 160 new trees, offering an unobstructed view of the Panthéon. Oaks were chosen as a tribute to those felled for the cathedral’s new roof, along with hackberries: “We chose all sorts of trees capable of withstanding summer temperatures five degrees hotter than today’s.”

Ateliers Luma before Bas Smets

Today, Bas Smets’ voice carries growing international weight. In March, he served on the Paris jury selecting the redesign for the Place de la Concorde. A month earlier, he spoke at a climate summit in Athens. There, he listened carefully to the city’s mayor: “He used terms politicians never used before, like ‘felt temperature’ and ‘rain river’ [runoff channeled by rainwater]. Southern Europe has understood that climate change is already here. Some summer days, the Acropolis must be closed because of unbearable heat. They’ve started radically rethinking their cities. They’re 20 years ahead of us. But even so, in Paris, we are now planting a lot of trees,” he concludes, ever the optimist.

Ateliers Luma after Bas Smets

(I recently conducted two interviews with Bas Smets a year apart, the first of which appears here.)

Support independent art journalist

If you value Judith Benhamou Reports, consider supporting our work. Your contribution keeps JB Reports independent and ad-free.

Choose a monthly or one-time donation — even a small amount makes a difference.

You can cancel a recurring donation at any time.