Rare privilege

A substantial exhibition devoted to Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) is always a major event. The colossal force of the Aixois master’s work rarely disappoints. So having the opportunity to see several exhibitions of the artist in quick succession is a rare privilege. After the remarkable presentation in Aix-en-Provence last summer, which focused on Cézanne’s native countryside yet revealed extraordinary inventiveness, the Grand Palais in Paris will, from 23 September, explore the painter’s vast legacy and its reverberations into the contemporary period.

Final Years

In the meantime, the Fondation Beyeler in Basel turns its attention to a distinctly modern Cézanne, concentrating on the final phase of his career, when, in the late 1880s, he abandoned the orthodox rules of representation.The major exhibition, on view through 25 May, brings together 79 paintings, including 21 delicate watercolours. In Basel, the artist whom Picasso famously called “our father to us all” more than lives up to expectations.

His wife, her portrait

At first glance, one might be unsettled by the seemingly traditional hanging, organised thematically, from still lifes to bathers. After all, Cézanne attached only relative importance to subject matter. Take the single portrait of his wife included in the exhibition. Painted between 1888 and 1890, it speaks neither of love nor even of affection, but presents a disembodied, egg-shaped head, fixed olive-like eyes, horizontal lines suggesting the back wall, and clashing colours: a dark blood-red dress, an aged yellow armchair, and several blues across the background.

In Cézanne works, the true subject is painting itself.

The task, again and again

Yet the series highlighted at Beyeler open our eyes to a crucial fact: the way the painter endlessly return again and again to the task. His new manner emerged through a set of recurring obsessions, one of which is the suspension of the gaze. He creates the mystery of what is missing, of anomaly, which perhaps unconsciously captures the viewer’s attention.

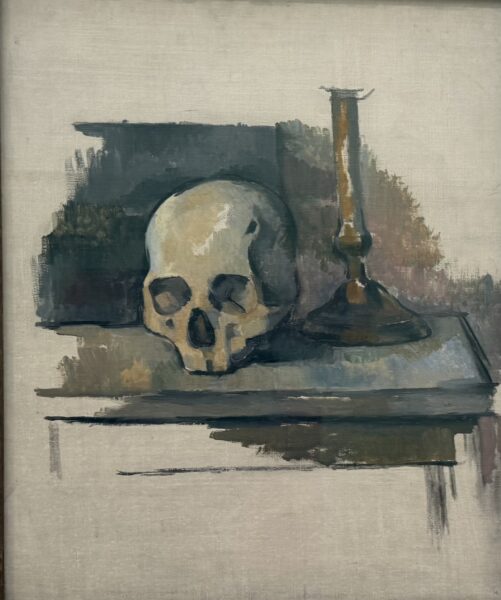

Stille lifes

The large room devoted to still lifes demonstrates this perfectly. It is not that Cézanne was clumsy; rather, the mischievous artist has arranged apples in precarious balance. The table tilts, the white tablecloth falls in folds that should send the fruit tumbling.

Ulf Küster

The exhibition’s curator, Ulf Küster, offers another example: The Card Players, of which five versions exist. Two are shown in Basel, on loan from the Musée d’Orsay and the Courtauld Gallery in London. “We see two peasants playing belote. Yet the game requires three players,” the curator insists.

Interminably long arm

Spot the mistake… The same applies to The Boy in the Red Vest (1888–1889), in which Cézanne depicts an interminably long arm, rendered in a range of bluish tones that resemble a landscape. “A head interests me, so I make it too large,” the modern painter would explain.

Translucent touches

Cézanne dares. In his landscape watercolours, he barely marks the white paper with his brush: a few translucent touches here and there. Almost magically, the forms of trees or mountains appear. The right gesture. The poet Rilke wrote of Cézanne: “Works of art are always the result of a risk taken, an experience carried through to the end, to the point where no one can go any further.”

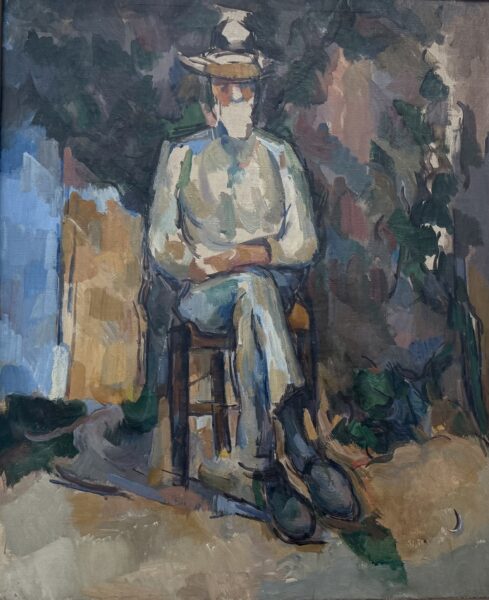

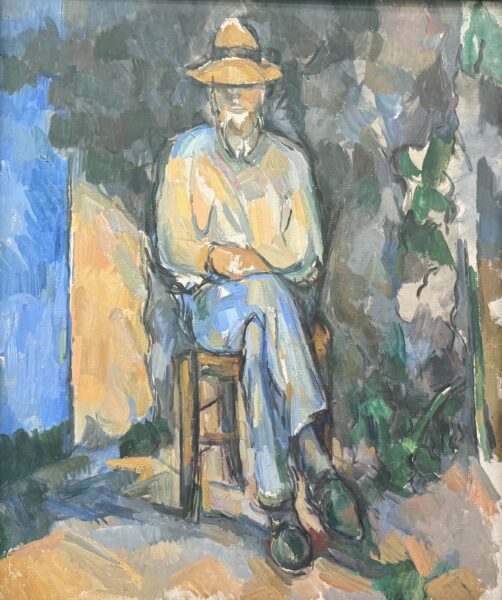

Emotional Summit

At the emotional summit of the Beyeler exhibition are three versions of the gardener Vallier, painted in 1906. The artist is nearing death. The shadows of the tree dance across the old peasant’s body in an Emotional suminterplay of yellows, blues, whites, greens and greys, articulated in three different propositions. Sublime.

Support independent art journalist

If you value Judith Benhamou Reports, consider supporting our work. Your contribution keeps JB Reports independent and ad-free.

Choose a monthly or one-time donation — even a small amount makes a difference.

You can cancel a recurring donation at any time.