Light obsession

For painters, light is an obsession. It is what gives life to a picture, sometimes to the point of provoking a mystical response.(Take for instance the light in Cézanne paintings, at the excellent exhibition currently on view in Aix en Provence. In Paris, Musée du Luxembourg is showing exceptional works on paper by the French abstract painter Soulages, driven by the very same obsession. Ill write about it soon).

La Tour and nothing else

If one artist mastered it with extraordinary brilliance, it was a Frenchman from Lorraine: Georges de La Tour (1593–1652). In his own lifetime he was already a star, working for the king of France, Louis XIII, who demanded that all other paintings in his chamber be removed except for La Tour’s Saint Sebastian, “of such perfect taste.” By the 20th century, La Tour would become one of the icons of world art. But in between? Incredibly, his genius lay forgotten for centuries, buried in the shadows of art history.

A real delight

Through January 25, 2026, the Musée Jacquemart-André is restoring this extraordinary artist to glory, with twenty of his works and another ten by his contemporaries. The exhibition is a delight, even if it is missing certain celebrated pieces, such as the Louvre’s Cardsharp with the Ace of Diamonds. One might assume that twenty paintings are too few to satisfy the visitor.

Gail Faigenbaum

Not so: La Tour’s entire known oeuvre numbers barely forty works. Here, the uncertainties of attribution are flagged along the way. “Experts continue to argue and to change their minds,” explains Gail Faigenbaum, the American co curator of the exhibition. “We lack tangible elements, such as documents about his training.” Nor is there any evidence that La Tour ever saw the work of his illustrious Italian predecessor, Caravaggio (1571–1610). Yet, like him, he worked according to the principle of painting through darkness.

The source of light

Among the most haunting works on display, on loan from the museum in Épinal, is Job Mocked by His Wife. Unlike Caravaggio, La Tour reveals the source of light: a candle placed almost at the center of the canvas. The composition is exceptionally inventive. Job, seated and crushed by misfortune, is confronted by his scornful wife, who towers over him. Faces emerge faintly from the gloom. The vermilion of her robe frames a scene otherwise composed of browns, blacks, and whites—a ghostly vision.

The great Newborn

Another breathtaking canvas on view at the Jacquemart, posthumously titled The Newborn, shows two women in shadow. The younger cradles a swaddled infant, her gaze entirely absorbed by the child. Light seems to emanate from the baby’s head. In profile, an older woman looks on. One hand appears to grasp a candle, the other shielding its flame. The work, held by the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rennes, bears no religious attributes—no halo. It is a timeless, universal scene of maternity with hypnotic force.

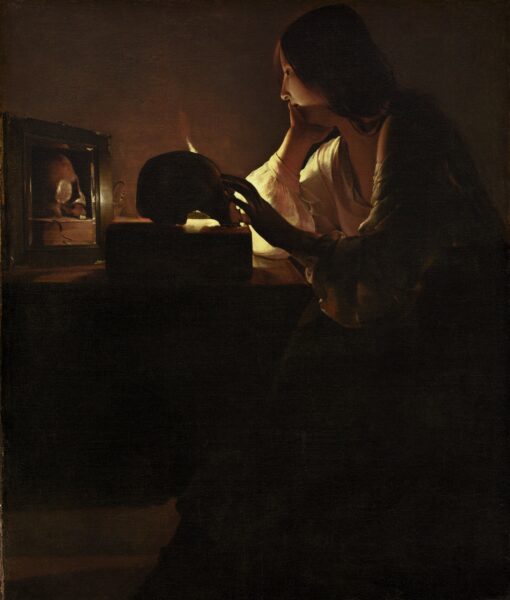

The poor and afflicted

La Tour was particularly drawn to stripped-down representations of the poor and afflicted. His Penitent Magdalene depicts the sinner in contemplation before a skull, reflected in a mirror. The painting long belonged to the famed family of French antiquarians, the Fabius—whose descendant, Laurent Fabius, would become Prime Minister of France.As his late brother François Fabius once told me,when they were children, they had the rare fortune of contemplating at home this learned meditation in chiaroscuro, before it was acquired by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, where it now normally resides.

www.musee-jacquemart-andre.com/fr

Support independent art journalist

If you value Judith Benhamou Reports, consider supporting our work. Your contribution keeps JB Reports independent and ad-free.

Choose a monthly or one-time donation — even a small amount makes a difference.

You can cancel a recurring donation at any time.