By tradition

By tradition, the English people have long harbored a visceral love for their countryside. For years, the archetype of this attachment was embodied by a sovereign—headscarf tied, Loden coat over her shoulders, dog at her side—wandering across one of her estates. In harmony with this passion for bucolic sensations, long before television ever broadcast intimate glimpses of Queen Elizabeth II, two men who had little in common were already vying, in the nineteenth century, for the representation of landscape across the Channel. One was J.M.W Turner (1775–1851), the other John Constable(1776–1837).

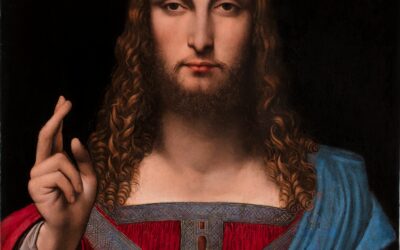

JMW Turner

National heritage

Today, both are regarded as absolute treasures of Britain’s national heritage. Tate Britain is devoting a major joint exhibition to them through April 12—an operation that qualifies as a national event. Yet for non-British visitors as well, this is a moment of pure delight.

Amy Concannon

The exhibition’s curator, Amy Concannon, maintains that there is still much to discover about these two giants. “Here we see that Constable is not only a painter of the countryside,” she explains. “He also depicts mountains and cities. And as for Turner, one would not expect him to represent India without ever having traveled there.”

Rivalry

JMW Turner

In a particularly touching way, the curator also defends both artists as though they were her own children, while not denying their rivalry. “In the early years, Constable was jealous of his contemporary’s precocious success, before eventually being admitted himself to the Royal Academy.” She nevertheless invites visitors to look differently at the two bodies of work: “I hope that when people leave the exhibition, they will feel they are of equal power.

John Constable

At first, viewers will be struck by the immediate impact of Turner’s paintings. Then, as they move closer to Constable’s works, they will become aware of his technique, the texture of his surfaces, and will apprehend his work in a new way.”

Turner, a virtuoso

JMW Turner

Turner, a virtuoso from a modest background, exhibited at the Royal Academy as early as the age of fifteen. He loved money and success, and he painted works that were deliberately recognizable. He took bold risks, even flirting with abstraction in his later years. But as Amy Concannon notes, “the late works are unfinished. As a result, we don’t really know how far he might have gone had he lived longer.”

Turner, dissolving representation

JMW Turner

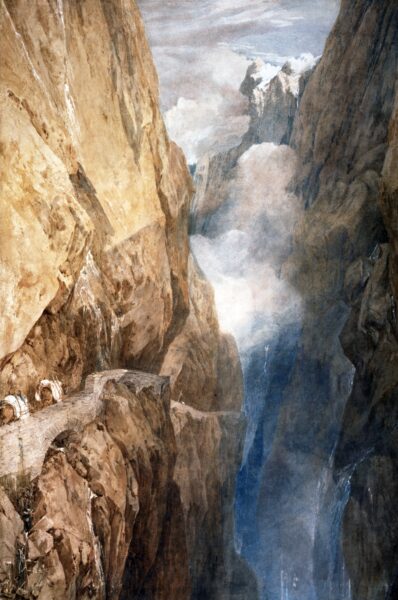

Constable, by contrast, was born into a prosperous family in Suffolk. His inspiration seems rooted in the “classical” Dutch landscapes of the seventeenth century. On one side, Turner dissolves representation, lends lyrical beauty to natural catastrophes on a grand scale, and plays with emptiness within the canvas—witness his extraordinary Snow Storm of 1842, which is nothing but the torment of the elements rendered in browns and blues.

Impasto compositions

John Constable

On the other, Constable builds thick, impasto compositions filled with numerous external elements—fictional figures, a bridge, a cart, or a small building. He makes something new from the old, as in The Leaping Horse (c. 1825), densely packed with detail despite a vast sky occupying nearly a quarter of the canvas.

John Constable

The genius on paper

John Constable

The exhibition’s ultimate rapture lies in the works on paper by both masters—pieces that, it should be noted, were never shown during their lifetimes. Constable’s cloud studies and Turner’s Venetian watercolors tell the next chapter of art history ahead of time: Impressionism and its climatic variations.

JMW Turner

Through April 12.

Support independent art journalist

If you value Judith Benhamou Reports, consider supporting our work. Your contribution keeps JB Reports independent and ad-free.

Choose a monthly or one-time donation — even a small amount makes a difference.

You can cancel a recurring donation at any time.