All black

Every color has its virtues. Black, when applied uniformly, unlike other hues, curiously gives relief to things. The great French figure of abstract painting, Pierre Soulages, understood this well when, at the end of his life, he created his “outrenoirs,” monochrome paintings worked through the depth of the material. Long before him, an American artist chose to express herself entirely in black. Her name was Louise Nevelson (1899–1988). She understood very early on that monochromy conferred plastic strength upon her works.

Born in Ukraine

Born Leah Berliawsky in Ukraine, she emigrated to the United States with her family at the age of six. Her surname changed with her marriage in 1920. In the 1930s and 1940s she experimented with various materials such as clay and wood. Black was already everywhere. In 1962 she represented the United States at the Venice Biennale with—anecdote has it, for lack of means—a work borrowed from her French gallerist, Daniel Cordier, who was also known as a major Resistance figure and close associate of Jean Moulin( central figure of the French resistance).

Bathed in bluish light

Through August 31, the Centre Pompidou-Metz is devoting an excellent retrospective to this artist, who became a classic of contemporary art in the 1970s and 1980s before being somewhat forgotten at the dawn of the new century. The works presented in Metz are of major importance, both in scale and in quality. The installation, largely bathed in bluish light, lends her work a striking dimension.However, the theory put forward by the curator, Anne Horvat, who consistently draws parallels between Nevelson’s work and contemporary dance, does not always seem convincing.

Modern dance

Of course, Nevelson declared in 1976: “Modern dance undoubtedly makes one conscious of movement, and it is that movement, coming from the center of one’s being, that allows us to generate our own energy.” Yet unlike other artists—Andy Warhol, for example, who collaborated with Merce Cunningham in 1968 on his “Silver Clouds,” floating silver balloon-like forms—the sculptor never worked directly with choreographers.

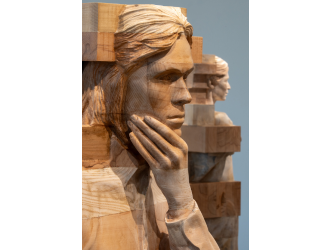

Arne Glimcher

Louise Nevelson’s longtime dealer, Arne Glimcher, founder of one of the most powerful galleries in the world, Pace, was present at the opening. “She was very close to Cunningham and to John Cage. But her work has nothing to do with movement. I believe Louise was influenced instead by Dada and Surrealist artists, beginning with Kurt Schwitters.”For her mature works are mainly composed of assemblages—what in the early twentieth century would have been called collage—of found wooden objects. She transforms them into kinds of bas-reliefs, puzzles made of the bric-a-brac of human history, unified by monochromy.

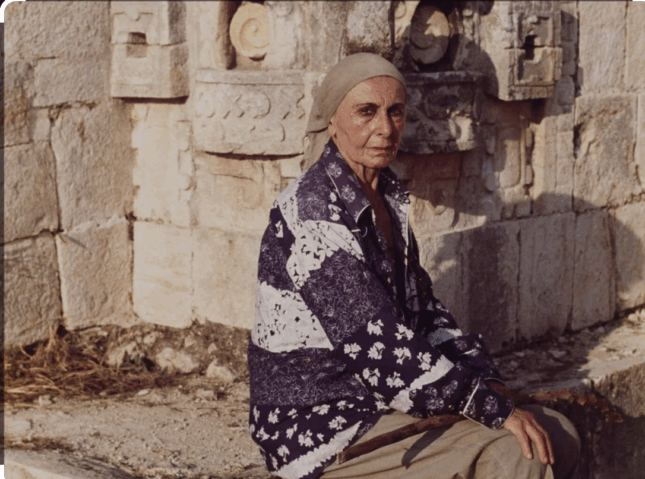

Ancient constructions

They evoke, among other things, ancient constructions built from strata of different periods. A photograph even shows Louise in 1981 standing before a Mayan wall at Uxmal, Mexico, which resembles a millennia-old version of her own work. One of the striking pieces in the exhibition, “Artillery Landscape,” was made around 1985. It consists of wooden crates that originally contained ammunition. The boxes, naturally repainted black, are scattered through the space, displayed half open. This three-dimensional composition creates the illusion of an aerial view of a city. Arne Glimcher, who owns the installation, comments: “This piece is a bit like a biblical legend: she transformed swords into tools of peace. Louise invented imaginary landscapes one can enter.”

Through August 31

“