Invention of a genre

On December 6, 2025, the English photographer Martin Parr died at the age of 73. It is fair to say ŌĆö and this is rare in contemporary photography ŌĆö that he invented a genre of his own, with his garish, satirical images of contemporary society.I interviewed him six years ago on the occasion of a commission he had received at the Ch├óteau de Versailles.

Quentin Bajac

For the past two years, Quentin Bajac, director of the Jeu de Paume in Paris, had planned to devote an exhibition to him. The emotion is therefore palpable for this first show, a posthumous tribute, on view through May 24.

It is not a retrospective but a thematic selection of 170 images drawn from the sprawling corpus of some 50,000 photographs that make up ParrŌĆÖs body of work. ŌĆ£I had in mind an exhibition focused on MartinŌĆÖs ŌĆśseriousŌĆÖ photographs, and he agreed to the idea”, Quentin Bajac explains. “In fact, since the 1970s his images have dealt, directly or indirectly, with the question of climate in Western society. At first he was somewhat reluctant about the project.

Critical dimension

Martin was never a whistleblower. He did not wish to appear more concerned than he had actually been. Yet over the past fifteen years, in interviews, he had become increasingly willing to address environmental issues. Behind the smile, there is a critical dimension.ŌĆØ This curatorial choice has, in effect, set aside the strand of his production celebrating British eccentricity ŌĆö the aspect that made him famous.

Portrait of a pigeon

Britain is nevertheless present, albeit in other guises. And while the theme is a serious one, one finds oneself suppressing a faint smile throughout the exhibition. There is, for example, a portrait of a pigeon in Brighton in 1998. It is about to attack a bag containing the cooked remains of one of its fellow birds. The bag is emblazoned with the words ŌĆ£Fried chicken.ŌĆØ

┬ĀShe is well done

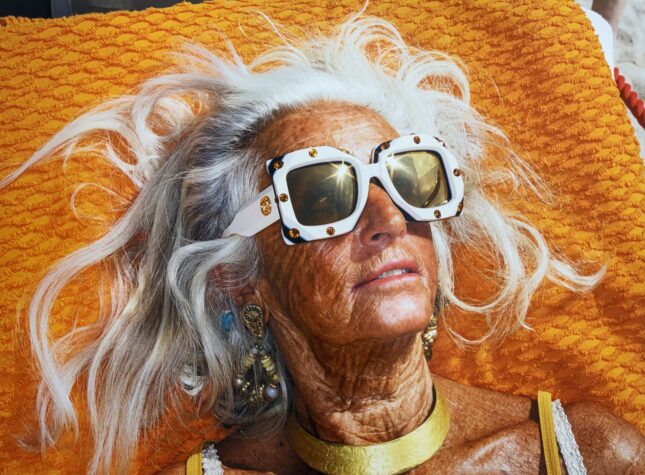

Not far away, another creature appears equally well done, captured in close-up by Parr: the face of an elderly woman, excessively tanned, still exposing herself to the sun in Cannes in 2018. Her enormous white sunglasses resemble two television screens. Her silver hair, spread over an orange towel, looks like tentacles. Back in 1983, in New Brighton, the photographer immortalized a bather lying on her stomach. Nothing would seem unusual ŌĆö except that she has chosen to position herself precisely in the shadow of a menacing steamroller.

Crime scene or beach scene?

Quentin Bajac points out that, as with this image, ParrŌĆÖs compositions are often more complex than they appear. ŌĆ£This beach scene could also be read as a crime scene: the body lies on the ground, arms limp, the victimŌĆÖs personal belongings scattered around her.ŌĆØThe beach ŌĆö with its exposed silhouettes and attendant leisure activities ŌĆö is one of Martin ParrŌĆÖs favorite subjects. It also provides an opportunity to highlight the mounds of waste generated by such pastimes.

Rubbish landscape

Again in New Brighton, a couple and their children have lunch beside a trash bin overflowing with rubbish. The greasy wrappers swirling around them do not seem to bother them. Parr also relished scenes exploring the relationship between humans and animals. In St. MarkŌĆÖs Square in Venice in 2005, a woman is photographed while taking a photograph.

Flying rats

Her face, however, is obscured by pigeons. Nicknamed ŌĆ£flying rats,ŌĆØ they have chosen her as their perch. In truth, the artist often presents his subjects in their least flattering light: garish lipstick smudged across teeth, protruding bellies, excessive consumption, absurd attitudes, distracted parenting.

┬ĀVoyeur

But where does Martin Parr stand? ŌĆ£On both sides,ŌĆØ replies Quentin Bajac. ŌĆ£He produces documentary photography deeply influenced by amateur photography. It is accessible to everyone. Parr does not seek to preach. He is a voyeur.ŌĆØ