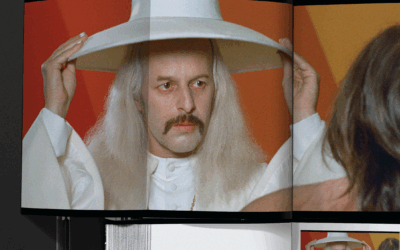

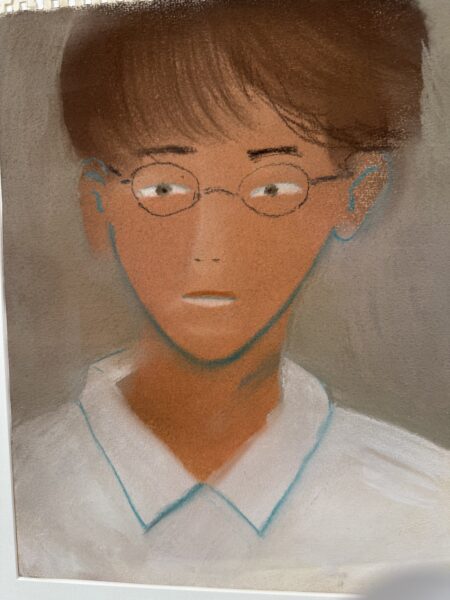

Quietly wise young man

Painting has a kind of magic: it can open onto other senses. This is the case with the canvases of Yu Nishimura (born in 1982), which almost always evoke silence—or sometimes the crackling of old screens that distort images. All this is imagined by the viewer… and then one meets the artist. Nishimura has the appearance of a quietly wise young man. He looks at you gently, and when he smiles, it is with the slightest movement of the mouth. The language barrier is very present, and the roughness of Western modes of expression may not suit him entirely.

Crevecoeur

He lives far from the sirens of the global art market, in Kanagawa (population 240,000), south of Tokyo. Yet in December 2025 he travelled to Paris. In the French capital, he is the subject of a major and remarkable exhibition at Galerie Crevecoeur, through 7 February 2026, across its spaces in the 7th and 20th arrondissements.

Success story

In 2018, Crevecoeur’s co-founder Axel Dibie discovered the artist—as one does in the 21st century—on Internet. Since then, the success story has only continued to grow. Nishimura is now also represented by the powerful multinational gallery David Zwirner, as well as by the excellent London gallery Sadie Coles HQ. Next year, he will have a retrospective in Paris at Lafayette Anticipations.

Solitude

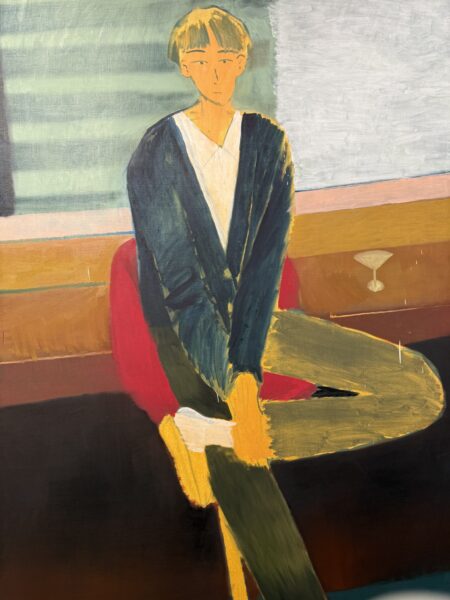

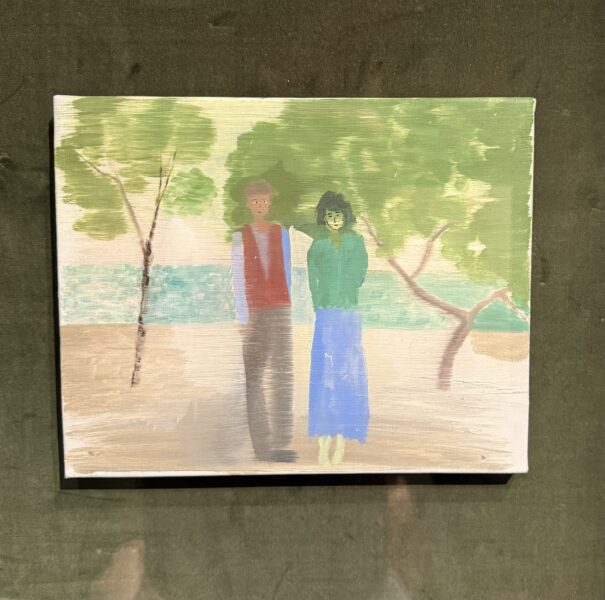

He says little about his daily life in the small city where he lives. What matters to him is solitude and the one-to-one relationship with painting—for the viewer, and for himself. In Nishimura’s work, solitude is not a source of sadness or affliction. Paradoxically, it gives rise to a certain sense of well-being. He paints many portraits of figures who appear isolated; a number of them, in fact, resemble him.

Luc Tuymans

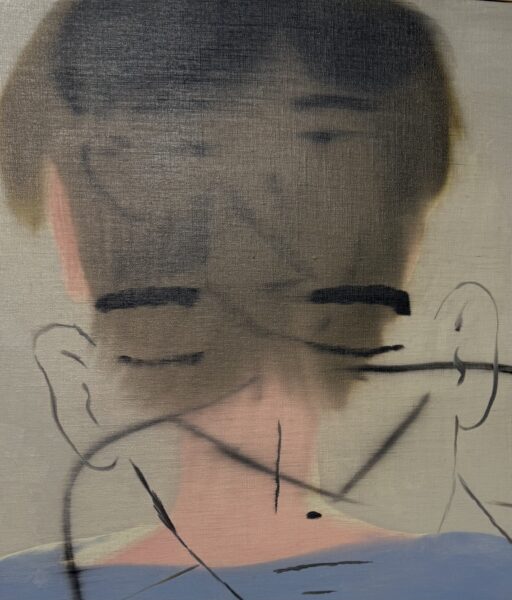

The compositions are slightly blurred, recalling the sensation of images seen on a screen. Among the painters who influenced him, he cites the Belgian artist Luc Tuymans (born in 1958), whose work itself reflects a reality mediated through screens. Nishimura also imagines superimposed portraits, rendered transparently, as if a single figure could be two people at once.

Nishimura embodies a form of contemporary Japanese pictorial romanticism.

The Great Wave

Today, the artist from Kanagawa—where Hokusai conceived The Great Wave, the masterpiece of Japanese woodblock printing—is a star of the ultra-contemporary art market. On 18 November 2025 in New York, Sotheby’s auctioned a large painting by the artist for €614,000. A very high sum, especially in a period of market uncertainty in contemporary creation—and, of course, a record price for Nishimura.

Waiting list

The 2.6-metre-high canvas depicts a young man dressed in contemporary clothing, standing in the middle of a dense autumnal forest. The palette unfolds in shades of russet, with an abundance of leaf motifs. A seductive painting. Today, according to Axel Dibie, the waiting list of collectors seeking to acquire works by Yu Nishimura from Crevecoeur is long. The Centre Pompidou and the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris already each own one of his works.

Spending time with him, one senses that his remarkable calm and discretion stand in sharp contrast to his recent, resounding success. When the subject is raised, Yu Nishimura simply replies: “It all depends on what you mean by success. It’s simply a source of motivation.”

What does the city of Kanagawa represent for you?

I was born in Kanagawa and grew up in Kanagawa. It is my everyday life. After graduating from university, I moved to the suburbs of Kanagawa. Gradually, I began to see the differences between Tokyo and Kanagawa.

The Great Wave by Hokusai refers to Kanagawa, doesn’t it?

Yes, that’s right. In reality, you can’t see Mount Fuji the way it appears in paintings. It’s true that Kanagawa is the place associated with ukiyo-e (literally “the floating world,” a reference to Japanese woodblock prints).

Does the fact that you live in Kanagawa, which is linked to one of the most important works in the history of Japanese art, influence you?

Yes, I think so. I think The Great Wave is highly formalized. It is quite far removed from a direct image of reality.

Of course, there are no waves like that. But isn’t it an expression of a permanent threat?

Yes, it’s like a tsunami.

In Japan, one always has the feeling of being under threat because of extreme weather and earthquake risks.

Yes, that’s true. There is always a threat. But when it becomes part of daily life, you don’t feel so much fear anymore. Earthquakes and tsunamis are things we live with in Japan. They are part of everyday life.

Is there such an idea of fragility or threat in your painting?

I think my paintings represent personal sensations more than natural threats.

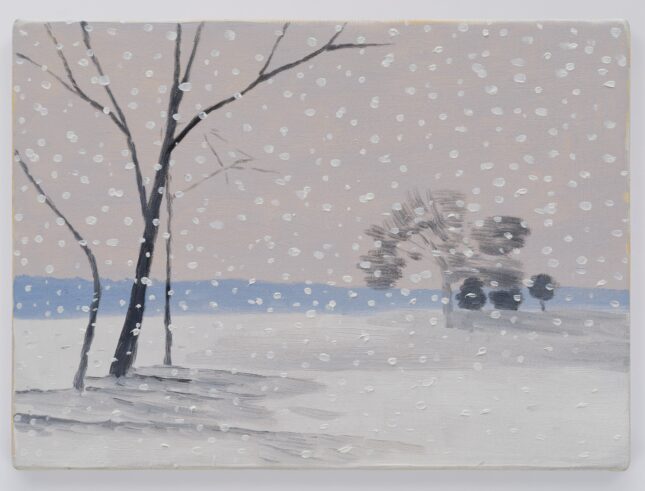

When we look at your paintings, we also have an impression of silence. Is Kanagawa conducive to silence?

I am always looking for a quiet place. I find it when I am alone—either in my head, or sometimes even when I am in a group, or simply in my room.

What is silence for?

I want people to perceive the one-to-one relationship between me and the painting. I want to create that state. I think it is best to establish a direct relationship between the painting and the viewer. Through the painting, I would like the viewer to find a form of silence. It is very personal. It is an exchange of silence.

Several texts suggest that your paintings give the impression of a moving screen, a moving image. Can you explain how you achieve that effect?

The work is done on a square surface, like a screen. What matters is knowing where to zoom in. The more I focus on a single point, the more important the surrounding forms become.

How do you technically achieve this?

First, I paint with a small brush. Then I blur the surface using a very large brush. I repeat this two or three times. I think I am creating a distance between myself and the object. I blur it, or make the object appear blurred.

At first glance, your painting seems very traditional—portraits and still lifes. But when you look more closely, because of your technique, it creates the illusion of seeing things through a screen. It feels very contemporary.

I’m glad to hear that.

Does manga influence your visual vocabulary?

Yes. But I think I absorbed everyday visual culture as a whole, and as a result I arrived at something that resembles Japanese manga. There may also be an unconscious influence.

The idea of seeing reality through a screen evokes the work of the Belgian painter Luc Tuymans. Was he important to you?

Yes. When I started painting at university, around the year 2000, I decided to become a painter and began thinking about a new way of painting. In Japan, there were the Superflat painters—Nara, Murakami… And at the same time, I was discovering very different Western painters. These two almost contradictory worlds formed the basis of my visual language.

How did you decide to become an artist?

I don’t think there was a single moment when I decided to become an artist. It was simply a practice that had been ongoing for a long time. At some point, I realized that I was a painter.

What did your parents do?

My father was a painter. He painted landscapes and figures. He was very influenced by Western art and worked in oil painting. He was also a good teacher, and his style was powerful. I was influenced by my father and took his work as a reference. He himself felt that his painting was perhaps too influenced by the West.

You are still young, but you have already achieved a great deal. How do you view your own success?

It depends on how you define success. I still feel it is not enough. But I am very grateful that Japan sees me as a new possibility within Asian art. My paintings have managed to cross borders and oceans. I think it is a situation for which one can only be deeply grateful.

Support independent art journalist

If you value Judith Benhamou Reports, consider supporting our work. Your contribution keeps JB Reports independent and ad-free.

Choose a monthly or one-time donation — even a small amount makes a difference.

You can cancel a recurring donation at any time.