Monumental David

Jacques-Louis David is a monument in more ways than one. Literally, because he painted on an extraordinary scale. Take one of his most famous works, permanently displayed in the Mollien gallery at the Louvre: The Coronation of Napoleon, a powerful hymn to the emperor’s grandeur, stretches a full ten metres in length. On seeing it, Napoleon is said to have exclaimed: “You can walk into this painting.”

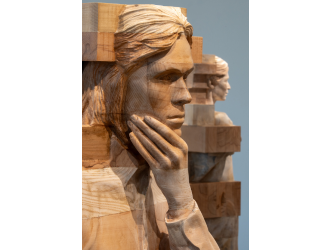

Visual shock

But David is also monumental in intent: his obsession was to create a visual shock in the viewer — what contemporary artists would now call a “wow effect.” David is that kind of painter, the one who stops you in your tracks with sheer force. There is little detour or disguise in his work, no delicate phrasing like chamber music that slips quietly into your ear. David is a full philharmonic orchestra unto himself.

Punch to the gut

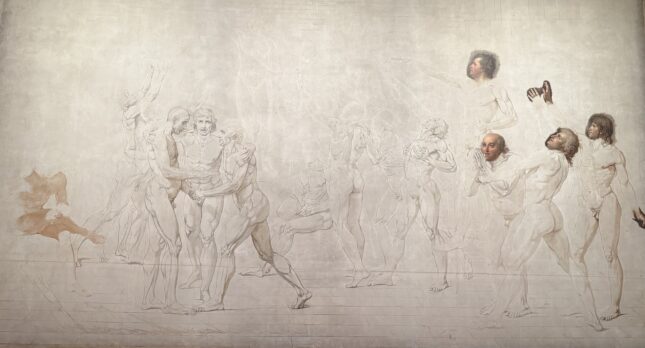

The retrospective devoted to him at the Louvre — the first since 1989 — makes this abundantly clear: some of his canvases hit like a punch to the gut. Not every one of the hundred or so works on view packs that kind of power, of course. In his pursuit of grandeur, David could also be an artist of great virtuosity but sometimes inflated tone, especially in his early years. His Oath of the Horatii (1784), with its grand, theatrical gestures evoking an ancient Roman stage, is considered by specialists to be the masterpiece of French Neoclassicism. On one side, the women lament, huddled together; on the other, the men raise their arms to swear their oath.

Sébastien Allard

David lived through six political regimes. The painting was made under Louis XVI —When the Revolution began to rumble — as a symbol exalting civic virtue. He was wholly committed, not only with his soul but with his political convictions (first revolutionary, then pro-Napoleonic). For him, painting — like everything else — was a matter of life and death. Did he not attempt suicide by refusing food in 1772 after finishing only second in the Prix de Rome? He finally won it on his fifth try. Then his politics grew more radical. “For David, art is not art for art’s sake — it’s a means of acting in the world,” explains Sébastien Allard, co-curator of the exhibition

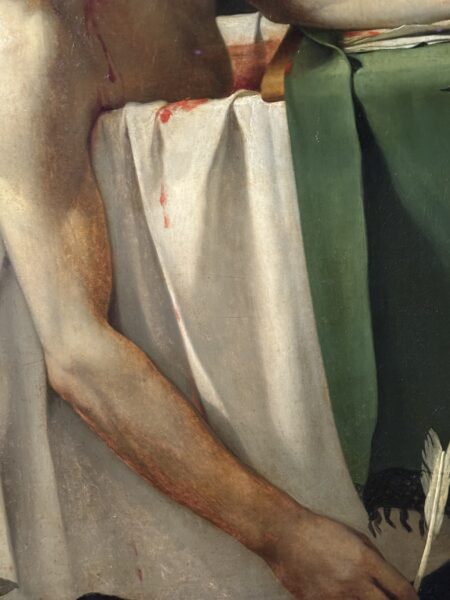

Crime scene

His absolute masterpiece, The Death of Marat (1793), has long since entered popular culture. “After the execution of Louis XVI, the Revolution needed new martyrs to venerate,” says co-curator Côme Fabre. “The painting was first shown in the Louvre’s courtyard on the day of Marie-Antoinette’s execution, then inside the Convention when the deputies met there. All of David’s pictorial mastery comes together in this work, which is at once a crime scene, a funerary portrait, and a proto-religious painting modeled on Caravaggio’s Entombment of Christ. The bathtub becomes a sarcophagus.”

Replicas for propaganda

At the time, David’s studio was extremely active; he had two replicas made for propaganda purposes. All three versions are reunited for this exhibition. The original now belongs to the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium — for in France the work soon came to be seen as a cursed symbol of revolutionary excess. In 1816, as a former deputy of the Convention, David was banished by the Restoration government. He went into exile in Brussels, where he died, leaving behind a formidable legacy through his pupils, among them Ingres.

As for the painting, it has now returned to French soil — but only until 26 January, the closing date of this powerful exhibition.

Support independent art journalist

If you value Judith Benhamou Reports, consider supporting our work. Your contribution keeps JB Reports independent and ad-free.

Choose a monthly or one-time donation — even a small amount makes a difference.

You can cancel a recurring donation at any time.