La Boheme

At the beginning of the 20th century, Montmartre was a territory of poverty and bohemia, filled with shantytowns, inhabited by street performers, circus people, “grisettes” and other hardworking little hands, as well as penniless artists who would become among the most illustrious figures of modernity.

At the foot of the Butte worked a young woman who was the first dealer for Picasso and for many others besides. Through January 26, the Musée de l’Orangerie is devoting an exhibition to her. It restores to the chronology—well before the celebrated Kahnweiler and Rosenberg—this missing link in the history of the art market. Berthe Weill (1865–1951) is finally placed back into the grand narrative of modernity.

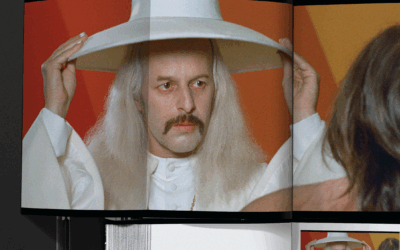

Marianne Le Morvan

“She was a childless woman, which for a long time, it must be said, was a handicap to her memory. In fact, when she opened under her own name in 1901, she put ‘B Weill’ on the sign, without stating her first name,” explains Marianne Le Morvan, the director of the Berthe Weill archives and co-curator of the exhibition, adding: “Yet she was the first true dealer in modern art. A pirate. At the time, she located herself geographically at the very heart of avant-garde creation.”

300 artists

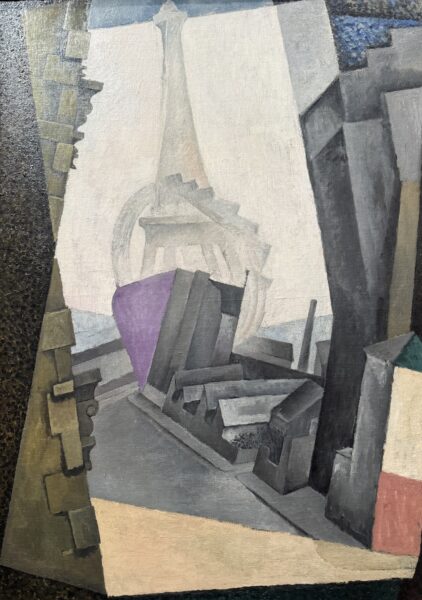

Diego Rivera

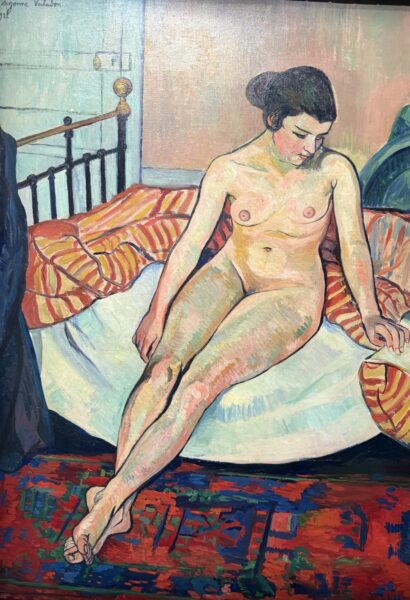

The roll call of works shown is striking: Picasso, Matisse, Modigliani, Valadon, and even Diego Rivera… In numbers, the activity of this dealer—the daughter of a ragpicker—amounts to 300 artists, four successive addresses, and a gallery that would close for good in 1941 after forty years in business.

Young Picasso

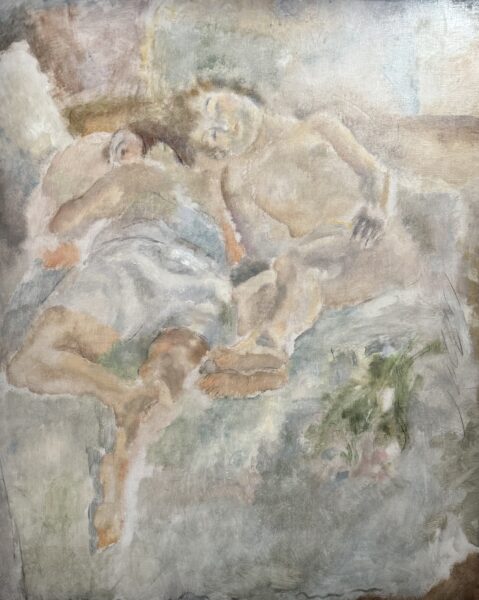

Suzanne Valadon

Thus, through the Catalan art agent Manach (or “Maniac”), she met Pablo Picasso even before her gallery opened. In 1942, she reminded him of it in a letter: “I think that today, 42 years ago (yes, my dear), I bought your first three paintings from you for 100 francs.” Among these, the curators—who carried out a colossal investigative effort—tracked down La fin du numéro (1901), a music-hall scene in pastel, strongly inspired by Toulouse-Lautrec, usually housed at the Picasso Museum in Barcelona.

Matisse

Henri Matisse

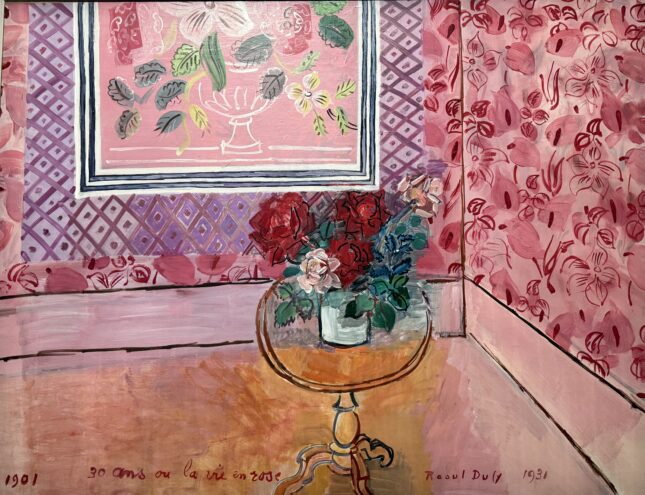

Weill showed Picasso in her space in 1902, including the remarkable Blue Period, without selling anything. This sounded the death knell of their commercial relationship. That same year, the young woman presented the work of Henri Matisse, then completely unknown to the gallery world. His forms were simplified. His blond colors burst forth, as in his Première nature morte orange (1899), where the atmosphere seems bathed in gold. Here again, sales success was not forthcoming. Berthe would write in her memoirs: “His restless mind as a seeker finds no credit among amateurs; the lack of sales proves it abundantly.” She persisted, also defending her friends from the Fauve movement—Marquet, Dufy, Vlaminck—featured in the exhibition. “The Fauves are beginning to tame the amateurs,” she comments.

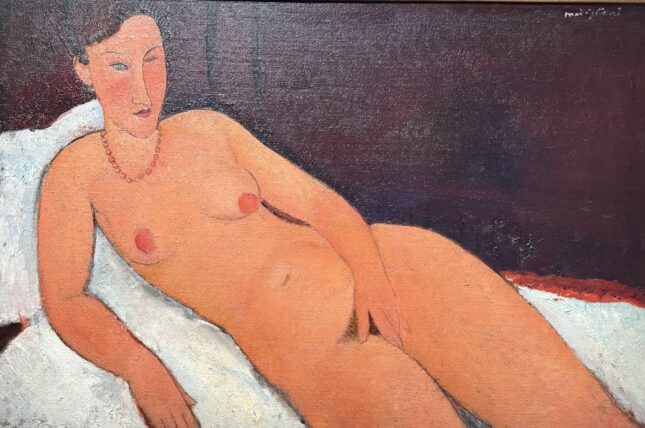

Four nudes by Modigliani

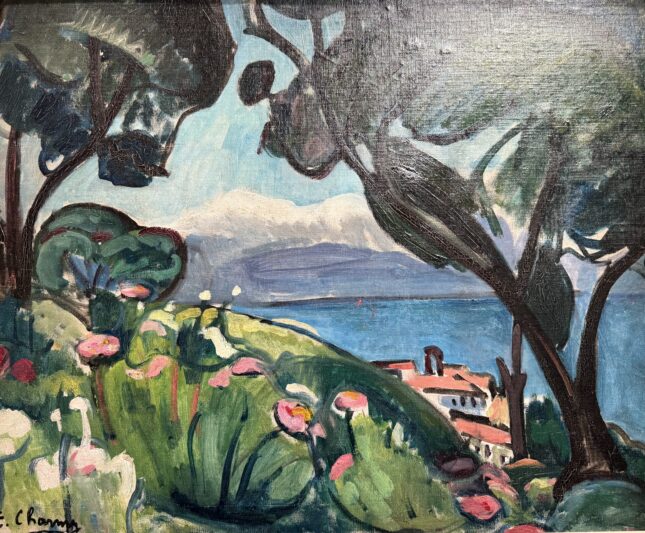

Berthe’s other great coup was the only exhibition ever organized for Amedeo Modigliani during his lifetime, in 1917, with four nudes that would cause a scandal: “sumptuous nudes, angular figures, flavorful portraits.” Yet there were no sales to show for it. The exhibition at the Orangerie also brings discoveries, such as Emilie Charmy (1878–1974), whose verve was just as Fauve.

Focused on Montmartre

Jules Pascin

But while this lady with thick spectacles and a low bun would always enjoy the affection of artists who became stars, she lacked the prestige and connections of the great dealers. An eye, yes; a large-scale business sense, no. If modern art invented a transatlantic art market, Berthe Weill would remain, for her part, the eye of Montmartre.

Emilie Charmy

Through January 26. www.musee-orangerie.fr/fr

Maurice de Vlaminck

Support independent art journalist

If you value Judith Benhamou Reports, consider supporting our work. Your contribution keeps JB Reports independent and ad-free.

Choose a monthly or one-time donation — even a small amount makes a difference.

You can cancel a recurring donation at any time.